The famous novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle. This novel of Russia before the Revolution is without question the masterpiece of Gorky, Russia's greatest living writer. Into one passionate, astonishing book has been gathered the spirit of the terrifying struggle against the Czar's autocracy. In it Russia stands forth in a flood of light.

- Locales: Russia

The Story:

The factory workers in the small Russian community of Nizhni-Novgorod were an impoverished, soulless, brutal lot. Their work in the factory dehumanized them and robbed them of their energy; as a result, they lived like beasts.

When the worker Michael Vlasov died, his wife, Pelagueya, feared that her son Pavel would lead the same anguished, brutal life. Gradually, however, she noticed with joy and apprehension that Pavel was turning out differently and that he was given to reading. One day, Pavel informed his mother that he was reading subversive literature and...

(The entire page is 2209 words.)

Table of Contents

- Part I

- Part II

Reader Reviews

Add your own review to this book!

Mother

By Juliet on July 15, 2010

It tells the story of a mother who takes after her son to socialism and works for it.She is kind and affectionate to her son and all his comrades. The story describes how the mother is transformed from a woman who afraid of her husband's beatings tries to make herself inconspicuous to a brave woman who trudges country roads and courts arrests to work for the cause. It her wish to be of use to her son which prompts her. She has seen her son mature into a leader, thoughtful, stern and respected. Like a mother, she loves and grieves for him but quickly takes to her new life of action. In disguise, she goes to many places taking books and leaflets. At her sons arrest and exile she goes to distribute his last speech in the court to the common people but is caught, arrested and dies in her struggle to be a message to the masses. All through we see her love for her son and her struggle to be a mother to him in his cause too. In her attempt she comes to love the comrades with whom she gets acquainted and does her best to take the new ideas of awakening everywhere.

http://www.classicreader.com/book/2178/

Maxim Gorky

Mother

Written: 1906

Source: Project Gutenberg 2001 (Etext #3783)

Transcription/Markup: Jarrod Newton/B. Baggins

Copyleft: Maxim Gorky Internet Archive (marxists.org) 2002. Permission is granted to copy and/or distribute this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License.Maxim Gorky explains Lenin's thoughts on this book:

"Now, the bald, r-slurring, strong, thickset man who kept rubbing his Socratic brow with one hand and pumping my hand with the other began to talk at once, with a kind twinkle in his amazingly alert eyes, of the shortcomings of my book Mother which he had, it appeared, read in the manuscript borrowed from I. P. Ladyzhnikov. I told him I had been in a hurry to write the book, but before I could explain why, Lenin nodded and himself gave the reason: it was a good thing that I had hurried because that was a much needed book. Many workers had joined the revolutionary movement impulsively, spontaneously, and would now find reading Mother very useful. "A very timely book!" That was all the praise he gave me, but it was extremely valuable to me. After that he asked in a business-like tone whether Mother had been translated into any foreign languages and what damage was done to it by the Russian and American censors. When I told him that the author was to be put on trial, he frowned, then threw back his head, closed his eyes, and gave a burst of amazing laughter..."

Maxim Gorky

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaFor other uses, see Maxim Gorky (disambiguation).

Maxim Gorky

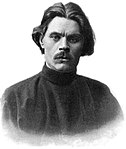

Portrait of Gorky, c. 1906Born Alexei Maximovich Peshkov

March 28 [O.S. March 16] 1868

Nizhny Novgorod, Russian EmpireDied June 18, 1936 (aged 68)

Gorki Leninskiye, Moscow Oblast,Russian SFSR, USSRPen name Maxim Gorky Occupation Writer, Dramatist, Political Activist Nationality Russian, Soviet Period Modernism Genres Novel, Drama Literary movement Socialist Realism

Signature Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (Russian: Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешков;[1] 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1868 – 18 June 1936), also known as Maxim Gorky (Russian: Макси́м Го́рький,IPA: [mɐˈksʲim ˈɡorʲkʲɪj]), was a Russian, Soviet author, a founder of the Socialist Realismliterary method and a political activist.[2]

Contents

[hide][edit]Life

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged andremoved. (July 2009) Gorky was born in Nizhny Novgorod and became an orphan at the age of nine. In 1880, at the age of twelve, he ran away from home in an effort to find his grandmother. Gorky was brought up by his grandmother.[2] Her death deeply affected him, and after an attempt at suicide in December 1887, he travelled on foot across the Russian Empire for five years, changing jobs and accumulating impressions used later in his writing.[2]

As a journalist working for provincial newspapers, he wrote under the pseudonym Иегудиил Хламида (Jehudiel Khlamida). The name is suggestive of "cloak-and-dagger" by the similarity to the Greek chlamys, "cloak").[3] He began using the pseudonym Gorky (literally "bitter") in 1892, while working in Tiflis for the newspaper Кавказ (The Caucasus).[4] The name reflected his simmering anger about life in Russia and a determination to speak the bitter truth. Gorky's first book Очерки и рассказы (Essays and Stories) in 1898 enjoyed a sensational success and his career as a writer began. Gorky wrote incessantly, viewing literature less as an aesthetic practice (though he worked hard on style and form) than as a moral and political act that could change the world. He described the lives of people in the lowest strata and on the margins of society, revealing their hardships, humiliations, and brutalization, but also their inward spark of humanity.[2]

Gorky's reputation as a unique literary voice from the bottom strata of society and as a fervent advocate of Russia's social, political, and cultural transformation grew. By 1899, he was openly associating with the emerging Marxist social-democratic movement which helped make him a celebrity among both the intelligentsia and the growing numbers of "conscious" workers. At the heart of all his work was a belief in the inherent worth and potential of the human person (личность, 'lichnost'). In his writing, he counterposed individuals, aware of their natural dignity, and inspired by energy and will, with people who succumb to the degrading conditions of life around them. Both his writings and his letters reveal a "restless man" (a frequent self-description) struggling to resolve contradictory feelings of faith and skepticism, love of life and disgust at the vulgarity and pettiness of the human world.

He publicly opposed the Tsarist regime and was arrested many times. Gorky befriended many revolutionaries and became Lenin's personal friend after they met in 1902. He exposed governmental control of the press (see Matvei Golovinski affair). In 1902, Gorky was elected an honorary Academician of Literature, but Nicholas II ordered this annulled. In protest, Anton Chekhov and Vladimir Korolenko left the Academy.

The years 1900 to 1905 saw a growing optimism in Gorky's writings. He became more involved in the opposition movement, for which he was again briefly imprisoned in 1901. In 1904, having severed his relationship with the Moscow Art Theatre in the wake of conflict with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, Gorky returned to Nizhny Novgorod to establish a theatre of his own.[5] Both Constantin Stanislavski and Savva Morozov provided financial support for the venture.[6] Stanislavski saw in Gorky's theatre an opportunity to develop the network of provincial theatres that he hoped would reform the art of the stage in Russia, of which he had dreamed since the 1890s.[6] He sent some pupils from the Art Theatre School—as well as Ioasaf Tikhomirov, who ran the school—to work there.[6] By the autumn, however, after the censor had banned every play that the theatre proposed to stage, Gorky abandoned the project.[6] Now a financially-successful author, editor, and playwright, Gorky gave financial support to the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party(RSDLP), as well as supporting liberal appeals to the government for civil rights and social reform. The brutal shooting of workers marching to the Tsar with a petition for reform on January 9, 1905 (known as the "Bloody Sunday"), which set in motion the Revolution of 1905, seems to have pushed Gorky more decisively toward radical solutions. He now became closely associated with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik wing of the party—though it is not clear whether he ever formally joined and his relations with Lenin and the Bolsheviks would always be rocky. His most influential writings in these years were a series of political plays, most famouslyThe Lower Depths (1902). In 1906, the Bolsheviks sent him on a fund-raising trip to the United States, where in the Adirondack MountainsGorky wrote his famous novel of revolutionary conversion and struggle, Мать (Mat', The Mother). His experiences there—which included a scandal over his traveling with his lover rather than his wife—deepened his contempt for the "bourgeois soul" but also his admiration for the boldness of the American spirit. While briefly imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress during the abortive 1905 Russian Revolution, Gorky wrote the play Children of the Sun, nominally set during an 1862 cholera epidemic, but universally understood to relate to present-day events.

From 1906 to 1913, Gorky lived on the island of Capri, partly for health reasons and partly to escape the increasingly repressive atmosphere in Russia.[2] He continued to support the work of Russian social-democracy, especially the Bolsheviks, and to write fiction and cultural essays. Most controversially, he articulated, along with a few other maverick Bolsheviks, a philosophy he called "God-Building",[2] which sought to recapture the power of myth for the revolution and to create a religious atheism that placed collective humanity where God had been and was imbued with passion, wonderment, moral certainty, and the promise of deliverance from evil, suffering, and even death. Though 'God-Building' was suppressed by Lenin, Gorky retained his belief that "culture"—the moral and spiritual awareness of the value and potential of the human self—would be more critical to the revolution's success than political or economic arrangements.

An amnesty granted for the 300th anniversary of the Romanov Dynasty allowed Gorky to return to Russia in 1913, where he continued his social criticism, mentored other writers from the common people, and wrote a series of important cultural memoirs, including the first part of his autobiography.[2] On returning to Russia, he wrote that his main impression was that "everyone is so crushed and devoid of God's image." The only solution, he repeatedly declared, was "culture".

During World War I, his apartment in Petrograd was turned into a Bolshevik staff room, and his politics remained close to the Bolsheviks throughout the revolutionary period of 1917. These relations became strained, however, after his newspaper Novaya Zhizn (Новая Жизнь, "New Life") fell prey to Bolshevik censorship during the ensuing civil war, around which time Gorky published a collection of essays critical of the Bolsheviks called Untimely Thoughts in 1918. (It would not be re-published in Russia until after the collapse of the Soviet Union.) The essays call Lenin a tyrant for his senseless arrests and repression of free discourse, and an anarchist for his conspiratorial tactics; Gorky compares Lenin to both the Tsar and Nechayev.[citation needed]

In August 1921, Nikolai Gumilyov, his friend and fellow writer was arrested by the Petrograd Chekafor his monarchist views. Gorky hurried to Moscow, obtained an order to release Gumilyov from Lenin personally, but upon his return to Petrograd he found out that Gumilyov had already been shot. In October, Gorky returned to Italy on health grounds: he had tuberculosis.

According to Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Gorky's return to the Soviet Union was motivated by material needs. In Sorrento, Gorky found himself without money and without fame. He visited the USSR several times after 1929, and in 1932 Josef Stalin personally invited him to return for good, an offer he accepted. In June 1929, Gorky visited Solovki (cleaned up for this occasion) and wrote a positive article about that Gulag, which had already gained ill fame in the West. Later he stated that everything he had written was under the control of censors[citation needed]. What he actually saw and thought when visiting the camp has been a highly discussed topic[citation needed].

Gorky's return from Fascist Italy was a major propaganda victory for the Soviets. He was decorated with the Order of Lenin and given a mansion (formerly belonging to the millionaire Ryabushinsky, now the Gorky Museum) in Moscow and a dacha in the suburbs. One of the central Moscow streets, Tverskaya, was renamed in his honor, as was the city of his birth. The largest fixed-wing aircraft in the world in the mid-1930s, the Tupolev ANT-20 (photo) was namedMaxim Gorky in his honor.

On October 11, 1931 Gorky read his fairy tale "A Girl and Death" to his visitors Josef Stalin,Kliment Voroshilov and Vyacheslav Molotov, an event that was later depicted by Viktor Govorov in his painting. On that same day Stalin left his autograph on the last page of this work by Gorky: "Эта штука сильнее чем "Фауст" Гёте (любовь побеждает смерть)"[7]( "This piece is stronger than Goethe's Faust (love defeats death)". In 1933 Gorky edited an infamous book about the White Sea-Baltic Canal, presented as an example of "successful rehabilitation of the former enemies of proletariat". With the increase of Stalinist repression and especially after the assassination of Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Gorky was placed under unannounced house arrest in his house near Moscow.

The sudden death of Gorky's son Maxim Peshkov in May 1934 was followed by the death of Maxim Gorky himself in June 1936. Speculation has long surrounded the circumstances of his death. Stalin and Molotov were among those who carried Gorky's coffin during the funeral. During the Bukharin show trials in 1938, one of the charges was that Gorky was killed by Yagoda's NKVD agents.[8]

In Soviet times, before and after his death, the complexities in Gorky's life and outlook were reduced to an iconic image (echoed in heroic pictures and statues dotting the countryside): Gorky as a great Russian writer who emerged from the common people, a loyal friend of the Bolsheviks, and the founder of the increasingly canonical "socialist realism".

[edit]Depictions of Gorky

The Gorky Trilogy is a series of three feature films: The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, My Apprenticeship, and My Universities, directed by Mark Donskoi, filmed in the Soviet Union, released 1938-1940. The trilogy was adapted from Gorky's autobiography.

[edit]Adaptations

The German modernist Bertolt Brecht based his epic play The Mother (1932) on Gorky's novel of the same name. Gorky's novel was also adapted for an opera by Valery Zhelobinsky in 1938. In 1912, the Italian composer Giacomo Orefice based his opera Radda on the character of Radda from Makar Chudra.

[edit]Gallery

[edit]Selected works

- Makar Chudra (Макар Чудра), short story, 1892

- Goremyka Pavel, novel, 1894

- Chelkash (Челкаш), novelette, 1895

- Malva, short story, 1897

- Sketches and Stories, stories, (three volumes) 1898-1899

- Creatures That Once Were Men, stories in English translation (1905)

- This contained an introduction by G. K. Chesterton[9]

- Twenty-six Men and a Girl, short story, 1899

- Foma Gordeyev/The Man Who Was Afraid (Фома Гордеев), novel, 1899

- Three of Them (Трое), novel, 1900

- The Song of the Stormy Petrel (Песня о Буревестнике), poem, 1901

- Song of a Falcon (Песня о Соколе),short story, 1902

- The Mother (Мать), novel, 1907

- The Life of a Useless Man, novel, 1907

- A Confession (Исповедь), novel, 1908

- Okurov City (Городок Окуров), novel, 1908

- The Life of Matvei Kozhemyakin (Жизнь Матвея Кожемякина), novel, 1910

- Tales of Italy, stories, 1911–1913

- My Childhood (Детство), Autobiography Part I, 1913–1914

- In the World (В людях), Autobiography Part II, 1916

- Chaliapin, articles in Letopis, 1917[10]

- Untimely Thoughts, articles, 1918

- My Recollections of Tolstoy, 1919

- My Universities (Мои университеты), Autobiography Part III, 1923

- Through Russia, stories, 1923

- The Artamonov Business (Дело Артамоновых), novel, 1927

- Life of Klim Samgin (Жизнь Клима Самгина), unfinished novel series:

- The Bystander, novel, 1927

- The Magnet, novel, 1928

- Other Fires, novel, 1930

- The Specter, novel, 1936

- Reminiscences of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Andreyev, 1920–1928

- V.I. Lenin (В.И. Ленин), reminiscence, 1924–1931

- The I.V. Stalin White Sea - Baltic Sea Canal, 1934 (editor-in-chief)

[edit]Drama

- The Philistines/The Smug Citizens/The Petty Bourgeois (Мещане), 1901

- The Lower Depths (На дне), 1902

- Summerfolk (Дачники), 1904

- Children of the Sun (Дети солнца), 1905

- Barbarians, 1905

- Enemies, 1906

- The Last Ones, 1908

- The Reception'/Vstrecha, 1910

- Queer People/Eccentrics, 1910

- Vassa Zheleznova, 1910

- The Zykovs, 1913

- Counterfeit Money, 1913

- The Old Man/The Judge/Starik, 1915, revised 1922, 1924

- Workaholic Slovotekov, 1920

- Somov and Others, 1930

- Yegor Bulychov and Others/Egor Bulychev, 1932

- Dostigayev and Others, 1933

[edit]Sources

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521434378.

- Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0413525201.

- Worrall, Nick. 1996. The Moscow Art Theatre. Theatre Production Studies ser. London and NY: Routledge. ISBN 0415055989.

- Figes, Orlando. 1998. "A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891-1924" Penguin, NY and London. ISBN 9780140243642

- Giuseppe Mario Tufarulo- La luna é morta e lo specchio infranto- Miti letterari del Novecento, vol.1- G.Laterza, Bari, 2009( Critica letteraria).ISBN978-88-8231-491-0.

[edit]Further reading

- The Murder of Maxim Gorky. A Secret Execution by Arkady Vaksberg. Enigma Books: New York, 2007. ISBN 978-1-929631-62-9

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

- ^ His own pronunciation, according to his autobiography Detstvo (Childhood), was Пешко́в, but many reference books have Пе́шков.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Maksim Gorki". Kuusankoski City Library, Finland. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ "Maxim Gorky". Library Thing. Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ "Горький Максим :: Биографии :: РефератБанк :: Рефераты, курсовые и дипломные работы, доклады, сочинения. Скачать бесплатно." (in Russian).

- ^ Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko had insulted Gorky with his critical assessment of Gorky's new play Summerfolk, which Nemirovich described as shapeless and formless raw material that lacked a plot. Despite Stanislavski's attempts to persuade him otherwise, in December 1904 Gorky refused permission for the MAT to produce his Enemies and declined "any kind of connection with the Art Theatre." See Benedetti (1999, 149-150).

- ^ a b c d Benedetti (1999, 150).

- ^ "Scan of the page from "A Girl And Death" with autograph by Stalin". Retrieved 2009-07-21.

- ^ New Orleans Media

- ^ Creatures That Once Were Men, and other stories, by Maksim Gorky (introduction) at ebooks.adelaide.edu.au

- ^ The manuscript of this work, which Gorky wrote using information supplied by his friend Chaliapin, was translated, together with supplementary correspondence of Gorky with Chaliapin and others, in N. Froud and J. Hanley (Eds and translators), Chaliapin: An Autobiography as told to Maxim Gorky (Stein and Day, New York 1967) Library of Congress card no. 67-25616.

[edit]External links

Find more about Maxim Gorky on Wikipedia'ssister projects: Definitions from Wiktionary

Images and media from Commons

Learning resources from Wikiversity

News stories from Wikinews

Quotations from Wikiquote

Source texts from Wikisource

Textbooks from Wikibooks

- Works by Maxim Gorky at Project Gutenberg

- "Anton Chekhov: Fragments of Recollections" by Maxim Gorky

- Some works of Maxim Gorky in the original Russian

- Works by Maxim Gorky (public domain in Canada)

- "Prince of Russian Literature" (Sri Lanka)

[show]People from Russia Categories: 1868 births | 1936 deaths | People from Nizhny Novgorod | Soviet novelists | Soviet non-fiction writers | Soviet dramatists and playwrights | Socialist realism writers | Russian novelists | Russian dramatists and playwrights | Russian short story writers | Soviet short story writers | Russian memoirists | Bolshevik finance | Capri | People buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis | Recipients of the Order of Lenin

No comments:

Post a Comment